The Tower: A Chronicle of Climbing and Controversy on Cerro Torre, by Kelly Cordes: Review an

by Cam McKenzie Ring

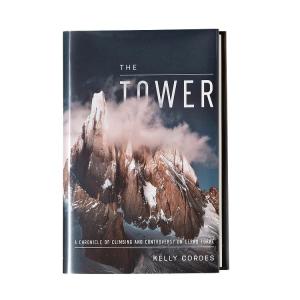

The Tower, by Kelly Cordes , is the latest release from Patagoniaís small publishing arm. The cover of the book is a beautiful photo of the Chalten Massif, speckled in ice and snow and partially covered by a nebulous cloud. This alone tells you much of what you need to know about the history of Cerro Torre, a magnificent mountain continually obscured by controversy and doubt.

It was purportedly first climbed in 1959 by Cesare Maestri and Toni Egger, who lost his life on the ďdescent,Ē according to Maestri and their basecamp aide, Cesarino Fava. Maestri and Fava concocted a wild report about the route Maestri and Egger climbed, and have stuck to that tale for over 50 years. Subsequent ascents of the mountain quickly disproved their claims, with no artifacts from their supposed climb visible on the upper two thirds of the tower. Their ďascentĒ has been the fodder of much speculation and even fights over the years, with Maestri himself adding fuel to the fire by returning to Cerro Torre in 1970 with a compression drill and placing over 400 bolts on the southeast ridge, creating the infamous ďCompressor Route.Ē

This route and the huge number of bolts, unnecessary in most places, was seen by many as a degradation of the mountain. In 2012, when Canadian Jason Kruk and American Hayden Kennedy completed the first ďfair meansĒ ascent of the southeast ridge, they decided to remove many of the bolts on the way down. This act created a firestorm for these young climbers, both in El Chalten and on online forums back home. The Tower chronicles all of these events and more, combining interviews with many of the players involved and the firsthand knowledge that comes from Cordesí own exploits on the mountain.

This book is a must read for anyone interested in the history of Cerro Torre, and the history of alpinism in general. It comes with two 16-page color photo inserts, and if the stories and pictures within donít stoke your fire for the alpine world, you should probably stick to the gym. The book can be purchased here for $27.95, or if you prefer a quick overview of the story narrated by Cordes himself, this 9 minute video covers all the basics.

|

| Cover photo by Mikey Shaefer/Patagonia |

Cordes, a Patagonia Ambassador and 4-times Mugs Stump Award winner, took a break from his own exploits to answer some questions for us about The Tower.

While there has been a lot written about Maestriís antics over the years, there were still things that hadnít been reported. The story of Cerro Torre is bigger than Maestri, and I wanted to try and capture some of that, even though the book is Maestri-centric. Heís Cerro Torreís most famous celebrity, which really makes no sense since he never stood on top of it, but he did bring something interesting to this mountain. Ermanno Salvaterra is the true king of Cerro Torre, if you want to talk about someone who has really put their time in and done the most routes. I think that the story of Cerro Torre is so complex that it goes well beyond Maestri and I just got interested in all of it. I have a personal history there and climbed the mountain myself, and then what really had it come to my mind as a book project was when Jason and Hayden removed many of the bolts from The Compressor Route in 2012. The way that people reacted and responded to their actions seemed outsized to me, but then so is everything about Cerro Torre. It seems to be a pinnacle for human behavior.

You reference the similarities to the Lance Armstrong doping scandal in the book. (Everyone wanted to believe in Lance and the idea of a ďhero,Ē even as the evidence amounted disputing that.) According to Tyler Hamilton, one way that Lance and his team members justified their actions to themselves at the time was that so many others on the tour were doping as well, so it could hardly be seen as cheating. Do you think this played into Maestri and Favaís deceit? Were other notable mountaineers of the time lying about or exaggerating their ascents?

Itís an interesting thought. Whether other people were telling big lies at the time, itís hard to know for sure. We have this thing in climbing of always taking people at their word and assuming that somehow climbers are above the bad behaviors that other humans do, like lying, and I think this is an absurd notion. I donít think there is anything about being a climber that makes us immune to lying and cheating and so forth. People do these things and climbers are no exception, and I suspect that we get duped a lot more often than we think.

When I was speaking with people during my research for the book, including an Italian professor who helped me as a translator, she and others were amazed when I told them that climbing is all self-reported, and that no one really checks on you and itís all about the honor system. People just thought that was kind of ridiculous and I think it is too. Thereís really is no other way to do it though Ė Iím not suggesting that we should be wearing some satellite transmitter to prove where we were Ė but it is really curious that this code of honor in climbing is held up as something that everyone adheres to when in fact a lot of people lie and I donít think climbers are the exception.

The thing with Maestri is that itís not hard to imagine that he was mourning his dead climbing partner and coming up with this story to give Egger somewhat of an honorable death, and as a brilliant side benefit it attaches him to what would have been the greatest climb in history. Itís kind of hard to call someone out when their partner died Ė all of a sudden youíre the jerk Ė and back then climbing was very seriously tied to machismo and the ideas of honor and so forth. I think it was hard for people at first to call him out on it in public, although there were initial doubters because that climb was so astronomical. The ascent was so far ahead of its time as we saw by it taking 47 years with attempts from the best alpinist from each generation for that face to finally be climbed.

We can never predict the future, and so they had no idea that they would ever get busted or that anyone would even doubt them. Back then, and the culture that they were from, people believed the climber. Maestriís said time and time again that ďIf you doubt me you doubt the entire history of mountaineering,Ē which is a completely intellectually devoid argument. But nevertheless he just states it over and over and it points to that notion that was ingrained at the time, and they had no idea that anyone was ever going to go back to Cerro Torre and climb that route, or that in 2012 over 100 people would climb it. Itís unfathomable Ė it would have been like trying to predict the Internet in 1959. He had no idea that anybody would ever come along, no idea that anybody would ever know the truth, and when you think of it that way itís not that crazy to imagine how he thought he could get away with it.

|

| Kelly Cordes: author, climber, and bearer of the mullet |

Do you think this should also call into question the veracity of every other ascent that Maestri completed, particularly the solo ones?

I certainly wonder that, and I think a lot of other people do as well, though hardly anyone will say it out loud. But itís certainly a legitimate question. At the same time, you need to be careful when you say things like that because immediately people will jump on that and twist your words, and say that you are accusing him of never climbing. Without a doubt, Maestri was a great climber and anyone who ever climbed with him or watched him climb all attest to this. Whether or not he really did all those solo climbs that he said he did, especially when his story about the greatest ascent of his career is a complete farce, certainly makes me raise an eyebrow.

To an objective thinker, itís hard to give the guy much credibility when he tells such a big lie, and thatís the non-emotional response. You canít go saying that in the Trentino region of Italy. Human history is filled with issues that show that the evidence is no match for belief; thatís a defining human train unfortunately.

After Reinhold Messnerís book on Cerro Torre came out, Maestri supporters printed up t-shirts that said ďThis venal controversy kills alpinism.Ē Do you think this controversy is bad for alpinism, or is it keeping the ethical discussion alive?

I think it is important to examine issues of truth and ethics, and I think truth is an ethical issue. There is also the issue that Toni Eggerís family never received an honest accounting of how he died. I donít think anyone could convince me that this doesnít matter, even though his death was 55 years ago. If someone were to claim that addressing a controversy and looking for truth is detrimental to the spirit of alpinism, I would absolutely turn that around and say whatís detrimental to the spirit of alpinism is people who lie and people who create ascents that never happened, people who donít tell the truth about how someone died. I think this is detrimental to things that are much more important than climbing mountains.

In the book you mention the idea that alpinism is not a democracy. People have the right to create and destroy routes as they see fit, but also suffer the consequences. Do you think that Kruk and Kennedy deserved the amount of blowback that they received for removing the bolts?

In my opinion, they didnít deserve it. Of course, I have a personal opinion on it and I support the removal of the route. But this is not a black and white issue, no matter what someone says or how loud they say it, or whether they turn their caps on when they write it. Everybody agrees that the route shouldnít have been installed in the first place, but not everyone agrees that it should have been removed. My argument is simply that climbing has a self-regulating system, and if we want that system to continue we have to accept the things we donít like as well as the things we do like. Itís really amazing if you think about it that climbing works as well as it does. There are plenty of loose cannons in the climbing community, and yet not a whole lot of people go on massive bolting sprees or go and remove routes whether the route deserved to be there or not. But if we want it to truly be a self-regulating system, then the threat of someone removing your route if you did it in a way that goes against the unspoken rules of how you do things is essential.

Everyone who has ever gone to the Chalten Massif has done exactly what Maestri and Hayden and Jason did, in a sense, in that everyone does exactly what they want to do. They donít ask the Internet community, they donít ask the baker in town, they donít fly to Italy and ask Maestri. People do what they want to do and itís amazing that it works as well as it does. After I heard about the chopping I was surprised at how angry everybody got, and in some ways I think a lot of the anger was about things beyond these handful of ancient two-inch metal pegs up there on the mountain that no one even sees until they are right upon them. So much of the outrage over the bolt chopping was misdirected. Most of the things that you would read and hear from people were fairly nonsensical, things like ďThey didnít get permission.Ē Whose permission were they supposed to get? Yours? They should have sent you an email to ask you? They didnít have to ask anybody, just like Maestri didnít. Whether or not thatís sustainable in this day and age as more people go climbing and get into it, I donít know.

If you had been in their position would you have done the same?

I have thought about that, and I probably would not have chopped them. Thereís a part of me that actually is sort of sad that I wouldnít have done it, as I see myself aging and becoming perhaps a little bit more tame, a little less idealistic, and a little bit more cynical. Those are the reasons I wouldnít have done it myself, yet I support the removal of the bolts. I wouldnít want to deal with the fallout but I kind of miss that time in my life when I cared about climbing or anything so much that I was willing to do what I thought was right regardless of the backlash. Thatís one of the things that I admire in them, and in a very strange sort of way thatís what you have to admire in Maestri too, and one of the things that people really like about him. Heís a really complex character and while I donít respect what he did in 1959 or in 1970, and how he behaved, there is a part of me that loves his anarchistic nature. I think that all climbers can kind of relate to that and the interesting thing is that there are similarities in that anarchistic nature both in what happened in 1970 and then what happened in 2012.

One of the myths that persisted after the de-bolting was that locals were using the route for guiding and that it destroyed their livelihoods. But you state that this was completely untrue. How did that myth get started and persist?

How do some of the things that we hear out there get started? When people are angry they tend to be a little looser with the facts. Cerro Torre at the time had never been successfully guided and climbers are a miniscule portion of the 100,000 plus visitors that come to El Chalten each season. The town overwhelming makes its money from the non-climbing tourists, thought certainly there are climbers posted up there for the season. Even The Compressor Route was too hard for most clients. So it had nothing to do with the localsí income and everything to do with anger.

What do you think the future holds for Cerro Torre? More linkups and speed ascents, new difficult lines, or maybe even more free lines?

Iím not really that sure. I think there is plenty of room for new routes. Certainly the free climbing movement is continuing into the mountains and I wouldnít be surprised if at some point in the future the standard is to free the entire route and then itís almost considered not as great of an ascent if you donít free it. That just seems to be the way things are moving Ė the freeclimbing standards are getting so high. And now if people don t get it their first try people are starting to redpoint things on alpine routes, which is crazy! Iím not trying to knock anybody for pulling on gear Ė I do it myself Ė but I wouldnít be surprised at all if in the future those kind of ascents are subpar. The way people are trying to free routes is really impressive. People will probably continue to free old aid lines but even more impressive would be the establishment of new routes on Cerro Torre. Thereís plenty of room!

Previous

Previous