All It's Chalked Up to Be: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the White Stuff

by Paul Nelson

Some call it white courage. I call it chalk. -Dan Goodwin

Almost all of us use some sort of chalk for our hands as we attempt to push to our limits and beyond on the rock. It’s pretty simple– with dry hands, we have greater friction on smaller holds and can climb harder. But compared to other types of climbing gear, we really don’t think about chalk too much: we chalk up while resting, maybe give our fingers the "French blow," use chalk bags as fashion statements (that’s a whole other topic), and that’s about it. There are dozens of types of climbing shoes, harnesses, cams, and quickdraws, but really only a half dozen types and brands of chalk.

But if you think about it, chalk is a huge deal in climbing. Other than shoes, it is the only piece of climbing gear that directly aids in making climbing easier; cams, skinny ropes, gri gris, those are just there in case we fall, but chalk makes us climb harder. Even when we are attempting to onsight a route with no beta, we find ourselves looking for those obvious patches of white, perhaps punctuated by a tickmark, that indicate a good handhold coming up. And of course, like any other facet of climbing, the use (and perhaps abuse) of chalk comes up frequently in various stylistic and ethical debates, as we try to figure out just how necessary it is.

What is Chalk?

In terms of chemistry, climbing chalk is almost always some form of Magnesium Carbonate (MgCO3), although some climbing-specific manufacturers add other drying supplements to their recipes. Just in case you’re wondering, climbing chalk is NOT the same chemically as blackboard chalk, which nowadays is usually some form of the mineral gypsum (Calcium Sulfate). It is also not the same as the mineral called “chalk” that makes up iconic formations like England’s White Cliffs of Dover, which is Calcium Carbonate.

|

| I'll bet they've got GREAT friction, though. |

History

For millennia, athletes and warriors realized the importance of dry hands in maintaining their grips. Why do you think Russell Crowe was always wiping his hands with dust and dirt in Gladiator (Gladiators actually did this)? By the early twentieth century, gymnasts and acrobats were using chalk to aid in their aerial routines.

|

| Strength and Honor! And dry hands! |

However, early climbers did not use chalk, despite its obvious benefits. Climbing in the United States well into the 1960s focused more on getting to the summit of a formation rather than actually free climbing it, and most climbers fixated more on pitons and etriers as a means of getting up the rock than on their fingers.

In France, the bouldering culture at Fontainebleau realized the importance of dry fingers, but rather than chalk, made use of rosin (a solid form of pine pitch). This actually made their skin more tacky and sticky than dry, but nonetheless helped boulderers deal with sweaty fingers. Unfortunately, once rosin is smeared onto a hold, it turns the rock into a glassy surface that is even slicker than it originally was, and the only way to climb it is to use more rosin, which in turn makes the hold even slicker. For this reason, rosin is almost universally frowned on today.

The first American climber to use chalk regularly, however, was almost certainly the father of modern bouldering, John Gill. Coming from a gymnastics background, it was only natural that his use of gymnastic chalk helped him as he was pushed free climbing well into the v7/5.13 range.

By the late 60s and early 70s, California free climbers like John Long and John Bachar (who had bouldered with Gill) had discovered this new “secret weapon” as they pushed their limits on Yosemite and Joshua Tree granite, carrying it in specially made bags slung around the back of their waists.

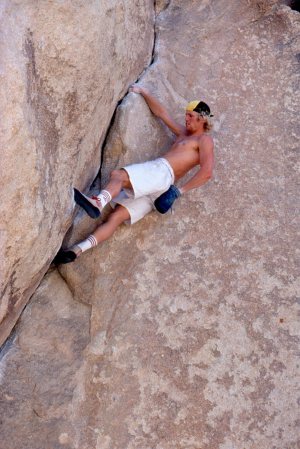

|

| John Bachar, Ropeless but not Chalkless on Joshua Tree's Spider Line (5.11+) |

Not all climbers in the 1970s adopted the use of chalk, however. As with every development in the sport, some believed that it made their own personal challenges too easy, and abstained from its use. Perhaps the most significant chalk abstainer was Henry Barber, who even today still prefers to climb without chalk, a seat harness, cams, or at times even shoes! Amazingly, Barber was climbing hard on his home crags in the Northeast, a climate of much higher humidity than Gill’s Colorado, or Long and Bachar’s California. He even made a famous “invasion” of Yosemite, where he ushered in the grade of 5.12 without the use of chalk.

Ethics and Style

The story of Henry Barber in a lot of ways is a great segue into the ethics and style of chalk use in today's world. As one of the first climbers to travel the world in search of great crags (as opposed to giant mountains), Barber had climbed at the high friction sandstone towers of Elbsandstein in Germany, where the use of chalk is forbidden even today.

In a lot of ways, the use of chalk is a perfect example of the distinction we climbers make between “style” and “ethics.” In climbing, “style” is seen as one’s personal approach to how they make climbing challenging to themselves. “Ethics,” on the other hand, have more to do with rules of climbing as they apply to altering the actual rock, and the experience of others on this rock.

Chalk can be both a stylistic and ethical foil. Barber preferred not to use chalk, because he believed it gave him an unfair advantage in his pursuit to climb routes “by fair means.” However, “fair means” and personal challenge has nothing to do with why chalk is banned at areas like Elbsandstein, or frowned upon at places like the North Shore of Lake Superior– other visitors might see it as unsightly, even pseudo-graffiti. Some areas in the United States, while not all-out banning chalk, have some restrictions on its use for these ethical, aesthetic reasons. Parks like Arches in Utah, and Garden of the Gods in Colorado, require climbers to use red-colored chalk so that their beautiful redrock formations are not smeared with white chalk.

Stylistically, a small minority of climbers today prefer to go without chalk for their own reasons. A friend of mine has climbed well into the 5.12 range at the humid crags of the Red River Gorge sans chalk. Years ago, when I climbed primarily at Indian Creek, Utah, my main partner and I decided that we did not need chalk in a desert with 0% humidity, and where the splitter cracks really didn’t require dry fingertips as much as many face climbs did.

You may want to try climbing without chalk, just to see how it works; you may surprise yourself and realize that a lot of chalk use is more psychological than actually practically necessarily. You can experiment with chalk alternatives like the EcoBall, Titegrip, or just cover your hands in sandy dirt Maximus-style!

Beyond the ethics of just dipping your hands into a bag of white courage, there are a few other issues related to chalk that we need to keep in mind. In bouldering, sport climbing, and even some trad climbing increasingly, the use of tick marks has really taken off in the last decade, often to the point of being ugly and ridiculous. A few years ago, there was even a climber at the Red River Gorge who was marking holds with different colors of sidewalk chalk before being harshly reprimanded by local climbers. And, for reasons of cleanliness and spill prevention, more than a few climbing gyms do not allow loose chalk, requiring climbers to use non-spilling chalk balls.

|

| Ticks Gone Wild, photo by rockclimbing.com user "areyoumydude." |

Types of Chalk

You've got quite a few options when it comes to buying chalk: blocks, powdered, balls, and even liquid. For the most part, all chalk, regardless of form, tends to be around $1/oz, or less if you buy it in bulk. Most major gear manufacturers have some sort of chalk line, as well, so the brand lists below are by no means exhaustive. Keep reading for more details!

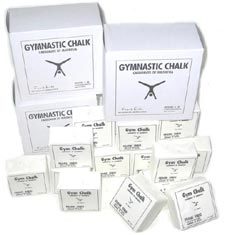

Blocks ($1-2 for a two-ounce block, also available in boxes of eight)You can get paper-wrapped solid blocks of chalk, usually about four inches square and an inch or so thick, which are easy to break up into whatever consistency you wish to have in your chalk bag.

|

| Frank Endo's Chalk Blocks |

Pros: These are probably the most economical option for chalk–especially if you buy them in bulk 8-packs, and a lot of folks think that blocks (myself included) do the best job of completely coating your hands.

Cons: They are messy! Usually, when you unwrap a block’s paper, chunks of it will fall everywhere, leaving tick marks all over your kitchen table. Furthermore, a block is usually a bit too big to fit completely into a chalk bag. Most climbers who use blocks unwrap them and then dump partially broken-up blocks into some sort of large plastic jar that can be taken to the crag.

Powdered (various bag sizes, usually around $1/ounce)

Want chalk that is finer and more consistent than you could ever get without throwing your blocks into a blender? Then you may want to get powdered chalk, which usually comes in a heavy duty re-closeable bag, or sometimes in a big jug.

|

| A bag of powdered Metolius Super Chalk |

Pros: This can be less messy than block chalk, and easier to get into your chalk bag.

Cons: My personal biggest complaint about powdered chalk is simply that you go through it too quickly. More of it clumps to your hands. Furthermore, it can result in bigger messes in your crag pack, since sometimes it is so fine that not even a closed chalk bag keeps chalk dust from getting all over everything.

Brands: Bison, Metolius Super Chalk, Black Diamond "White Gold."

Chalk Balls (Usually $4-$5 apiece, cheaper in bulk)

If you value cleanliness, or your gym does not allow loose chalk, then refillable chalk balls are the way to go. They are simply cloth balls with a closed end, which are filled with loose chalk. Most are also refillable with powdered chalk. Some climbers prefer to drop a chalk ball into a bag that already has loose chalk in it, or even to make their own chalk balls with old socks or nylons.

|

| Bison Chalk Ball |

Pros: Clean, and definitely the most economical, since you waste very little chalk. Some are refillable.

Cons: If you are a heavy sweater, or climb in hot, humid places on slippery rock, a chalk ball is probably not going to give you enough coverage. They can also fall out of your bag while climbing; I cant count the times that I've seen a chalk ball plummeting towards me as a belayer, the panic that ensues as I think "rock, rock ROCK!" and then the relief as the chalk ball lands with a little "poof."

Brands: Bison Balls, Black Diamond "Chalk Shots" (non-refillable)

Liquid Chalk (Around $12 for a 200 ml bottle)

Many climbers like to coat their hands with liquid chalk: basically powdered chalk that is suspended in some sort of quick-evaporating alcohol solution. Obviously you don't take this on a climb with you, but it does a great job of giving your hands a uniform coat of chalk right before you jump on your project. It is definitely pricier than the above chalk options, and you'll still need to take block, powdered, or chalk balls on your climb (unless you're a boulderer). Also, if you're the DIY-type, there are a few recipes for making your own liquid chalk floating around the internet.

|

| Liquid Chalk |

Pros: Completely coats your hands, giving you a good chalky "base" before you start your climb.

Cons: Expensive, requires other chalk types to accompany it.

Brands: Petzl "Power Liquid", Edelweiss Liquid Chalk, Mammut Liquid Chalk.

There are a few other variations on chalk that this article does not cover. Joshua Tree Climbing Salve also has a whole line of herb and spice scented chalks, if you're into that sort of hippie thing, and Atomik even makes scented chalks that have numbing agents in them, in case you can't take the pain of your project's micro-crimpers.

In the end, no matter what type of "White Courage" you use, the end goal is the same: climb harder!

4 Comments

Add a Comment

Add a Comment

|

dagibbs 2014-10-13 |

"Other than shoes, it is the only piece of climbing gear that directly aids in making climbing easier;" Well... I'm going to have to suggest that tape or crack-gloves also directly aid in making your climbing easier when crack climbing. |

|

munky 2014-10-14 |

Cocaine!!!!! (Chappelle) |

|

joeforte 2014-10-28 |

I love the problem solving skills that climbing requires. When all of the holds are chalked, it ruins that experience. Also, chalk often cakes up holds, making the friction worse. One of my pet peves is when someone dips into their chalk bag and goes directly to the rock without blowing or wiping off the excess. That layer of dust under their hands is just going to make things harder! Arno Ilger (The Warriors Way) helped me break away from chalk use. My hardest onsight was chalkless, (12c) and now I never use it. |

|

mojomonkey 2014-11-11 |

Sometimes I see folks chalk their shoes. It makes me smile. |

Previous

Previous